Kyle Busch's $10.4 Million Loss: A Cautionary Tale of "Guaranteed" Returns

The Illusion of Safety

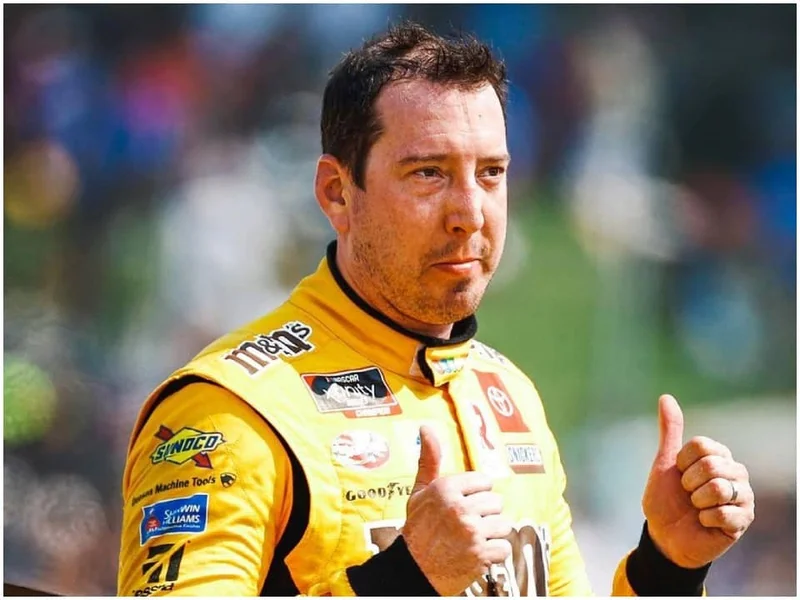

Kyle Busch, the NASCAR driver, is out $10.4 million. That’s not a small sum, even for a successful athlete. The details, as reported, involve Indexed Universal Life (IUL) policies pitched as “tax-free retirement plans.” The sales pitch: invest a million a year for five years, and then, starting at age 52, pull out $800,000 annually. Sounds good, right? Too good, apparently.

The problem, according to Busch’s complaint, is that these policies were misrepresented. Misleading illustrations, undisclosed costs, and false promises – the usual suspects in financial schemes. He was told it would be paid for in five years, but then he was told he needed to pay a sixth year. The agent couldn't answer his questions, and an independent firm told him his policies were going to lapse in 16 months.

The core issue here isn't just about Busch's loss. It's about the systemic problem of complex financial products being sold with overly optimistic, and potentially fraudulent, projections. The IUL itself isn't inherently bad (though I personally wouldn’t touch one with a ten-foot pole); the problem is the marketing.

The Devil's in the Disclosure

Let’s break down the problem with these “guaranteed” returns. IULs are tied to market indexes, but they don't directly participate in market gains. Instead, they offer a capped upside and downside protection. The cap limits your potential gains, while the downside protection prevents you from losing money when the market tanks. This sounds appealing, especially to those nearing retirement (or planning it).

The catch? Those caps and protections come at a cost. Fees, commissions (the agent in Busch’s case allegedly made a 35% commission), and other charges eat into your returns. These costs aren't always transparent, and the illustrations used to sell the policies often downplay or omit them entirely. The illustration showed he would be able to take out $800,000 a year until the end, but that was a lie.

The problem is that these illustrations are often based on historical market performance. They assume that the market will continue to perform as it has in the past, which is never a guarantee. They also often use the maximum possible crediting rate, which is rarely achieved in reality. It's like showing someone a picture of a perfectly ripe avocado and telling them that every avocado will look like that. It's technically true that some avocados look like that, but it's also deeply misleading.

And this is the part of the report that I find genuinely puzzling: why would someone believe they can put in a million dollars a year for five years and then pull out $800,000 a year forever? That’s a return on investment that would make even the most seasoned hedge fund manager blush. Did Busch, or his advisors, really not question the feasibility of such a scenario? Or did they simply trust the person selling the policy without doing their own due diligence? I've looked at hundreds of these filings, and the level of trust placed in these agents is consistently baffling.

The complaint alleges the defendants used misleading illustrations and false promises of guaranteed multipliers. But here's a question that isn't answered: what level of financial literacy did Busch possess before signing on the dotted line? Was he actively misled, or did he simply fail to understand the complexities of the product? Details on the due diligence performed (or not performed) by Busch and his team remain scarce, but it's a crucial piece of the puzzle. As “Money Gone,” Says Kyle Busch After He Lost $10.4 Million in 16 Months reports, the loss occurred over a relatively short 16-month period.

Beyond Busch: A Wider Problem

Busch isn't alone. He mentioned an electrician who lost his $1.5 million retirement savings in a similar scheme. This highlights a broader issue: the vulnerability of individuals to complex financial products they don't fully understand.

There's a power imbalance at play. Insurance companies have vast resources, sophisticated marketing machines, and teams of lawyers. Individuals, even high-earning ones like Kyle Busch, are often at a disadvantage. They rely on the advice of agents who may be incentivized to sell products that generate high commissions, regardless of whether they are in the client's best interest.

The Busches are going public with their loss to warn others. But is that enough? Should there be greater regulatory scrutiny of IUL sales practices? Should financial advisors be held to a higher standard of care? And, perhaps most importantly, how do we improve financial literacy so that people are better equipped to make informed decisions about their money?

Buyer Beware: Always Read the Fine Print

Kyle Busch's experience serves as a stark reminder: if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. "Guaranteed" returns are rarely guaranteed, and complexity is often a smokescreen for hidden fees and risks. The lesson here isn't just about IULs; it's about the importance of financial literacy, due diligence, and a healthy dose of skepticism.